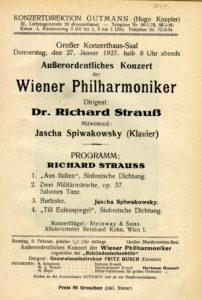

His Master’s Voice

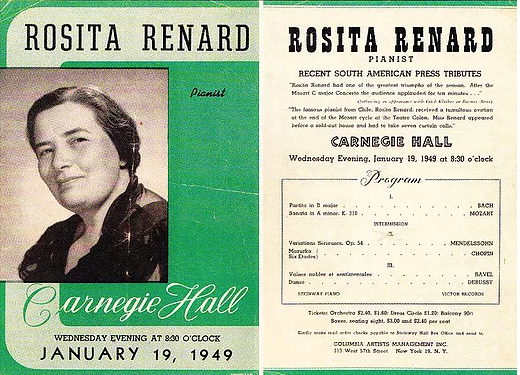

Recording technology has had a profound impact on the musical world. Before we could preserve sound documents, music needed to be played and heard (ie, experienced) ‘live’, whether in the home, a salon, or a hall. The earliest recording devices were financially out of reach for most consumers and of such poor quality that they could hardly be considered a replacement for a concert experience. Things began to change as the technology improved: as music lovers could hear longer works such as sonatas, concertos, and symphonies on gramophone records and on the radio, the need to go hear great works in concert began to diminish. The setting in which music was heard was no longer necessarily where the music-making took place, the audience member no longer needing to be in the presence of the performer. One could listen in the comfort of one’s home without even seeing another person – including the musician.

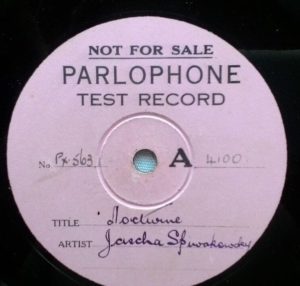

In the medium’s first several decades, no editing was possible: what you heard was exactly what the artist had played. Both early cylinders and flat disc recordings were produced by a needle carving the groove that the playback needle would traverse to reproduce the performance. Commercial discs were pressed from a metal stamper that replicated the engraved ‘master’ disc and so there was no way to correct a wrong note or other inaccuracy. Each disc in the days of 78rpm records was essentially a ‘live performance’ (once that speed became the standard, each 12-inch side held 4 to 5 minutes of music), so artists would make multiple takes to produce the best one to be released (sometimes it required a dozen or so takes – sometimes just one). Audiences at the time were accustomed to the occasional wrong note, as might also be heard in a concert performance, though of course artists aimed both in the studio as well as on stage to give as accurate a reading as possible. However, at the time there was no expectation – initially at least – that pristine precision was a key component of what would be considered a worthy performance, either in concert or on record.

Increasing Permanence

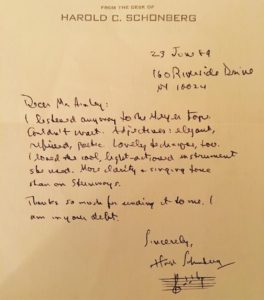

Tape technology changed all of that. The methodology was initially developed in the 1930s – there are some early German tape recordings of classical musicians in concert dating back to 1937 and many more from during the war (including a 1944 stereo tape performance of Walter Gieseking playing Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto) – but the process was only more widely adopted in 1948 when Columbia produced the first LP (long-playing) records which used tape to record the initial performances; EMI began using this process more widely in 1950, having experimented with tape recording in 1949. Once this more flexible material was used and the recording session didn’t require the cutting of a master disc, there was the potential to ‘erase’ incorrect notes by splicing the tape of one take of an artist’s performance with that of another before pressing the final record. When done well, the editing process could create a seamless performance that was note-perfect; whether the resulting pastiche was musically consistent was another matter, as was whether it accurately represented a musician’s true capabilities. New York Times music critic Harold C Schonberg recounted the tale of a young pianist who in the early days of the LP was recording the Chopin Concertos but couldn’t play the entire thing without any fumbles. He was reassured that the engineers would be able to combine different attempts of the passages together and that he need not worry. When listening to the playback, the pianist turned to the conductor and said, “It’s pretty good, isn’t it?” The conductor replied, “It’s very good, my boy. Don’t you wish you could play like that?” [While this is how the story was reported by Schonberg, the work in question was actually the Franck Symphonic Variations – the pianist was Paul Badura-Skoda and the conductor was Artur Rodzinski; these artists also recorded the Chopin Concertos together.]

With this technology allowing for artists to record precise readings of large-scale works that could be listened to uninterrupted in high-fidelity sound, the recorded performance began to be seen as more of a permanent artistic statement as opposed to a kind of provisional account. Of course, there were those who were very aware that their discs might be a kind of testament to their artistry to be left for the posterity, it can be postulated that not all artists considered their discs to be as enduring as they now are and probably did not expect that they would be listened to a century or so later. Alfred Cortot set down his first account of Chopin’s Preludes in 1926, but then began to record the cycle again in 1927 (he finished this newer account in 1928 but the set was never issued). Cortot would record the works again in 1933, 1942, and 1957, most likely not expecting that earlier versions would still be sought after and listened to – certainly not almost a century later.

Sanitized Performances

I believe that the fact that Cortot began to record them again one year after his 1926 account was released suggests that perhaps he did not see his records at the time as ‘everlasting’ – which could also explain why he released records with more wrong notes than did most of his contemporaries. (It is worth noting that several great pianists have stated that Cortot’s wrong notes were better played than many pianists’ correct ones.) Today, an artist would not consider allowing a recording to be issued with even a single wrong note. Indeed, even concert recordings that are commercially released are often ‘patched up’ with takes from a follow-up session: this was the case with Horowitz’s 1965 Carnegie Hall recital (he made a fumble in the opening moments of the first work on the programme) and the practice has continued. So are you really hearing a live performance when you hear a CD of a concert performance? Not always.

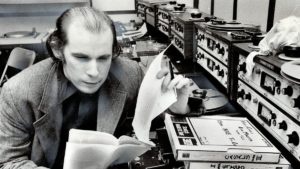

Glenn Gould famously retired from the concert stage to focus on recording, with a very conscious intent to create an ‘ideal’ interpretation on records that would represent his vision of a given work. Part of his process involved using the technology to adjust levels and balances to be more to his liking than what he was producing himself. This was a sign of the artist taking the wheel of that ‘don’t you wish you could play like that’ sentiment by being part of the creative process in the studio.

The extent to which the recording process could be used to create something different than would be heard in concert was clear to me when I had the opportunity to attend a recording session of the Montreal Symphony Orchestra around 1989. I was sitting in the recording booth and while the orchestra played works by Debussy, the producer followed the score calling out the instruments that were about to enter, in response to which an engineer boosted the microphone levels for those instrument groups. I was stunned: what happened to the conductor’s role in creating a cohesive balance amongst the musicians? Furthermore, the fact that multiple sections were separately mic’ed from others meant that one would hear an overlay of these groupings rather than the blend of instruments one would hear in concert – which is how the composer had intended the music to be heard. In other words, what listeners would hear at home would in no way resemble what would be heard in the hall. Modern recordings, in their quest for a ‘clean’ and ‘perfect’ reading, were creating something completely different than what a pair of human ears would pick up in a live performance.

Where To Listen?

If recordings could be so clean as to be note-perfect and sonically beyond reproach – both to a degree that one would likely not experience in a live performance – does it not follow that the concert hall might seem less attractive to some music lovers? What with having to dress for the occasion, get to the hall and deal with parking, tolerate people who might cough or unwrap candies during performances, with only top-tier tickets providing a decent view of the performer(s) … doesn’t listening in the comfort of one’s own home seems much more inviting? Particularly as technology improved and one could hear with a level of precision far beyond what could be heard in the hall, the home listening experience became very appealing. But it also created in listeners an unrealistic expectation of what a musical performance truly is.

There is something far more problematic with how recordings impacted the live music experience: the audience-performer relationship is out of the equation when hearing a recording, the emphasis being on listening to a performance but not being part of an experience that is shared in time and space with both the musician(s) and others in the audience. At home, you listen in a space different from that where the musician gave their performance, as well as at a different time. While I am of course, given my interest in historical recordings, delighted that we can listen to musicians of the past who we could not have heard in the concert hall because of our disparate timelines, there is no doubt that the habit of listening at home can create a different perception of the musical performance experience, separate from a particular set and setting. Additionally, a level of anonymity became part of the dynamic of listening to great music: listeners did not see a musician in front of them and in fact need not even know what they looked like. Listening to music at home, one could do what one wanted while the commodity of music was presented in the background, as opposed to being front-and-centre in your experience.

It is apparently for this reason that Rachmaninoff refused to allow his live concerts to be broadcast. Stating that the radio “makes listening to music too comfortable,” Rachmaninoff believed that “to appreciate good music, one must be mentally alert and emotionally receptive. You can’t be that when you are sitting at home with your feet on a chair.” He added another factor which is particularly important and frequently overlooked: “An artist’s performance depends so much on his audience that I cannot imagine even playing without one.” Despite the massive fees he was offered – and he made a fortune as a soloist already – Rachmaninoff refused to appear on the radio, refusing to play New York Philharmonic concerts on Sundays, the day they were broadcast. His contracts stated that if on any occasion a concert would be broadcast, the radio stations were to air his 1929 commercial recording of his 2nd Concerto during his performance. (One concert in which he played that was actually broadcast was the Sir Henry Wood 50th Anniversary of the Proms concert in 1938: however, they arranged the programme such that the concert opened with Rachmaninoff playing his C Minor Concerto so that the broadcast could begin after his live performance. He had refused the offer of an enormous sum for his performance to be transmitted over the airwaves.)

In The Moment

That Rachmaninoff should feel so strongly about not playing live while others listened ‘comfortably’ raises the question of how he reconciled this position with his extensive catalogue of commercial recordings. This has been the subject of discussion for decades and is well beyond the scope of this article. Perhaps he viewed the mechanical reproduction of a performance differently because he was not playing at the time that the audience was listening; yet he was also making recordings without an audience despite his having said that he couldn’t imagine playing without one, so one wonders how he was able to do so and whether he considered these discs any differently – and if these performances were at the same standard as those that he played ‘live.’ Many who heard him in concert said that his playing was in fact noticeably different in live performance than on disc, and we now have a glimpse of how different it might have been.

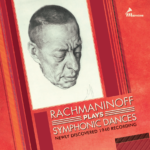

The recent discovery and release of Rachmaninoff’s read-through of his own Symphonic Dances at the piano in Eugene Ormandy’s living room finds him playing with much more spontaneity, dramatically forged phrasing, and marvellous lingering over phrases than we hear in his studio discs (which are still superb). The playing in this fly-on-the-wall recording is utterly mesmerizing and an absolute revelation, with a degree of inspired music-making and a level of intimacy in how the music is communicated that is simply staggering. As great as Rachmaninoff’s studio discs are, they pale in comparison to what we can hear in this precious document, an off-the-cuff moment that might have simply disappeared into thin air had it not been surreptitiously recorded. And yet this reading was not meant to be heard by others and isn’t an actual concert performance, though it gives great insight into his playing. As astonishing and perhaps even more so are a few precious minutes of a Brahms Ballade and Liszt Ballade from an actual 1931 concert performance captured by Bell Laboratories engineers (available in the same set as the Symphonic Dances) – while the sound is very poor, the power and intensity of Rachmaninoff’s playing is simply beyond belief and must be heard to be believed.

The Perils of the Studio

It should be evident that the mindset of performers playing in the moment is understandably very different than those who know they are creating something that will be heard over and over again. Something that will be heard repeatedly will be subjected to a different degree of scrutiny, and knowing this, the performer will be unlikely to play with the same level of abandon that they might in an inspired concert performance. I first heard this expressed at the MSO recording session I attended when after listening to one take in the booth, Dutoit said, “That was good for a live performance but not good enough for a recording,” and back in front of the orchestra he went to conduct another take.

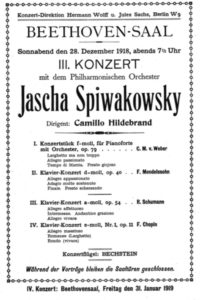

The process of recording that I witnessed at the MSO recording was very different than what artists went through in the days of direct-to-disc recordings. The further back one goes into recording history, the more challenging the process was, and the stresses that the system required in order to produce a record was one that hardly inspired the artist’s unbridled create expression. Ferruccio Busoni articulated in a letter to his wife the challenges he went through in his first recording session in 1919:

“My suffering over the toil of making gramophone records came to an end yesterday, after playing for 3 hours! I feel rather battered to-day, but it is over. Since the first day, I have been as depressed as if I were expecting to have an operation. To do it is stupid and a strain. Here is an example of what happens. They wanted the Faust waltz (which lasts a good ten minutes) but it was only to take four minutes! That meant quickly cutting, patching and improvising, so that there should still be some sense left in it; watching the pedal (because it sounds bad); thinking of certain notes which had to be stronger or weaker in order to please this devilish machine: not letting oneself go for fear of inaccuracies and being conscious the whole time that every note was going to be there for eternity; how can there be any question of inspiration, freedom, swing, or poetry? Enough that yesterday for 9 pieces of 4 minutes each (half an hour in all) I worked for three and a half hours! Two of these pieces I played four or five times. Having to think so quickly at the same time was a severe effort. In the end, I felt the effects in my arms; after that, I had to sit for a photograph, and sign the discs. – At last it was finished!”

It should be evident that with the Herculean pianist having had to go through this process, we would scarcely hear something representative of what he was capable of in concert. Additionally, he had recorded during the acoustical recording era, before the invention of the microphone: this system was in use prior to 1925 and required the instrument to be amplified through the use of cone-shaped horns (as illustrated in the image on the right), which drastically reduced the scope and fidelity of his sonority – and as Busoni articulated in his letter, he already needed to compensate for the inferior piano. While there is some magic that can be gleaned from his 26-minute discography from three years later (no discs were issued from the session detailed above), it is clear that great artist in such circumstances could not play with the same level of presence and command as they could in concert. Cramped, hot quarters of studios – with no audience – were hardly an environment conducive to artistic expression.

‘A Torture Chamber’

Busoni is not the only one who had such difficulties in the studio. Artur Schnabel went through a terrible ordeal a decade or so later when he began his now legendary cycle of Beethoven Sonatas – the first on record – at EMI’s Abbey Road Studios. Despite the fact that the microphone could now capture a more realistic sonority than was possible in Busoni’s time, not only was the recording process still challenging because works needed to still be split into 4-to-5-minute segments, but it seems that management still had very little idea of the stress of the process on a musician concerned about communicating their artistry:

This week was an ordeal, a torture chamber. “What does not kill me makes me stronger,” says Nietzsche. Hopefully (probably) this is true. I had no idea of how outrageous a process the recording on discs could be. Like slave drivers they burdened me with six hours of recording on a daily basis. I had to play pieces that were not included in the contract, but I had no time to prepare them. They thought I was always able to play all the Beethoven sonatas and concertos at the drop of a hat. Instead of refusing to do anything that was not prearranged, I let them, as usual, cajole me into doing it…. The act of violence against humans is mainly caused by the imperfection of the machine, which he has created. For example: one can only play for four minutes. In these four minutes sometimes 2000 or more keys are hit. If two of them are unsatisfactory you have to repeat all of the 2000. In the repeat the first faulty notes are corrected but two others are not satisfactory, so you must play all 2000 once again. You do it ten times, always with a sword of Damocles over your head. Finally you give up and 20 bad notes are left in it. I am physically and mentally too weak for this process and was close to a breakdown. I began to cry when I was alone in the street. Never before had I felt deeper loneliness. My conscience tortured me. Succumbing to evil, the betrayal of life, the marriage by death. It is perfect nonsense, totally unnatural. Depravity….

It is stunning to consider that Schnabel’s pianism is largely remembered for these recordings made in circumstances so poor that he was crying in the street after the sessions! I’m certain that those who have criticized his errors and rhythmic challenges in some of these performances have had no idea of the conditions he had to endure in committing these works to disc (and likewise, many who have praised them likely didn’t know either). That any magic could get through is indeed remarkable, but we might also wonder how beautifully he must have played play in a setting more conducive to inspired music-making.

The same applies to Alfred Cortot, who over the course of the five days from July 4 to 8, 1933 recorded Chopin’s 24 Preludes, 4 Ballades, 12 Etudes Op.10, 2nd and 3rd Sonatas, 4 Impromptus, 6th Polonaise, Fantaisie, Barcarolle, and Tarantelle. It is remarkable that he was able to produce such sumptuous accounts with such a gruelling schedule. It’s little wonder that there were some dropped notes, given that precision editing was not possible and he had that much music to get through in so little time, and yet there is exquisite beauty and inspiration in his playing. How to fathom, as with Schnabel, how he might have played in concert when he was at his prime.

The Dreaded Red Light

As technology improved and recording became easier, artists did not necessarily feel comfortable in front of the microphone, as the pressures to produce a polished performance that would stand up to repeated listening were the same, still running counter to the spontaneous in-the-moment experience of a live musical performance. Dame Myra Hess stated, ‘When I listen to my recordings, I feel I am going to my own funeral,’ and described how she too despised seeing that red light go on indicating that she was being recorded. Under duress she admitted that perhaps her recording of Beethoven’s Op.109 was perhaps rather OK – it is beyond sublime by most people’s standards, so one truly wonders what she would have considered to be an ideal performance. Her concert recordings are indeed on another plane, though her studio recordings are – despite her displeasure – of the highest artistic level by any era’s standards. Another British pianist, Solomon, said the same thing about the process: while he appreciated the benefits of records and broadcasting, he nevertheless said, “I don’t like being dictated to by lights, and told at this moment to be silent and ready to play, and when I’ve finished my performance feel that I don’t cough or something until the red light has gone off. It’s a very impersonal thing.”

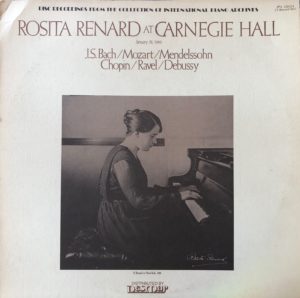

International Piano Archives founding president Gregor Benko was in the studio when Rudolf Serkin was recording Beethoven’s Hammerklavier Sonata. The pianist gave a run-through that Benko said was the most volcanic, spacious, mind-blowing performance he had heard (and he’d heard many) … and then when the red light went on, out from the pianist’s fingers came a completely different kind of performance, one that bore no resemblance to what he had played moments before. Benko was dismayed at the thought that no one would be able to hear what he had heard, that the record would be not even a pale shadow of what had come before. Indeed, early unofficial concert recordings of Serkin reveal that he was indeed be a very different pianist than the one represented on disc. I’ve found many of his studio recordings to have a nervous, somewhat unsettled quality, but the unbridled expansiveness of some concert performances – such as the one below – is of a completely different nature than his more known performances:

Varying Performances

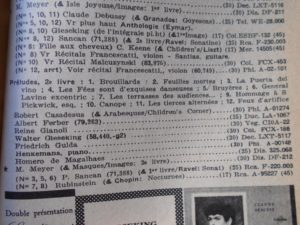

It is important to remember that musicians do not always play the same way – not just from concert to concert, but also as they and their artistry naturally evolve over time. I’ll never forget how a few seconds of a single recording completely shattered a perception that I had held about Jorge Bolet based on the later recordings I’d heard and also what others had said about him. At the time that I went to the aforementioned Montreal Symphony Orchestra recording sessions, I had been given the choice to attend either the orchestra’s Debussy recordings or some concerto recordings with Bolet. My friend in the orchestra who was arranging for me to attend suggested the Debussy session because he and many of his colleagues found Bolet’s playing to be slow and lacking fire; as I was not familiar with Bolet’s artistry (such as his staggering 1974 Carnegie Hall recital) and history (like the fact that he had played for Hofmann and heard Rachmaninoff in rehearsal and concert), I accepted his suggestion and therefore missed an opportunity to meet Bolet – one of my great life regrets. Years later, I was visiting Gregor Benko when Bolet’s name came up and the opinion that I’d had of him based on what I’d heard. He popped a cassette into a desktop tape recorder and out came the most expansive, volcanic, sky-opening playing of the Chopin-Godowsky Etude No.1 – in a style completely at odds with all of the Bolet recordings I had heard! The performance (still unissued) was made a year prior to the one below, but this traversal is very similar in temperament:

But what did those familiar with Bolet’s Decca recordings hear? Not the same kind of playing at all:

Intimate Music-Making

The Decca account is beautifully polished and elegant, but is completely lacking the vitality and bravura of the live performance. Sadly, Bolet is far more remembered for later recordings much like this one, not at all representative of him at the height of his powers. Several of his students have told me that he was at his best not only in his earlier years but in more intimate settings, such as after a lesson or a master class: he would often sit with one or many students to chat and play for an extended period of time, playing spontaneously and giving marvellous readings that went above and beyond what audiences heard. (The Chopin-Godowsky Op.10 No.1 that Benko had played me came from one such post-masterclass session at Curtis Institute, a 3-hour gathering that was captured on tape that has never been made publicly available.) Unfortunately, the recordings of Bolet that have circulated most have been the roughly 30 CDs he produced for Decca, when he was past his prime and less engaged in the studio and the recording process.

Bolet was not the only one played differently in more personal settings: the legendary Leopold Godowsky apparently shone in the salon more than he ever did in concert and certainly more than on disc. Abram Chasins recounted the experience of hearing Godowsky play at his home, and upon leaving his teacher – the great Josef Hofmann – said, “Never forget what you heard tonight; never lose the memory of that sound. There is nothing like it in the world. It is tragic that the world has never heard Popsy as only he can play.” And so with recording technology as well as concert performances, we are only exposed to a single snapshot of a performer – one that does not necessarily reveal their true abilities. Everyone can have an off-night yet based on a single concert we can crystallize our thoughts about an artist into a strictly-held impression – and the same certainly applies to recordings. Imagine how awful it would feel for you if someone’s impression of you was based on a single social interaction when you were not at your best (alas, this is in fact how it is for many of us) – how limiting, how inaccurate, how unfair. Unfortunately, it is human nature to define and harden our perceptions into held opinions based on our limited experience – but this is not always accurate. And this makes the job of the artist all the more challenging.

One pianist who recorded extensively but whose many records still do not reveal the scope of his playing is Michael Ponti: his Vox recordings circulated widely but unfortunately do not capture the vastness of his technical and musical gifts. It is only very recently that I came to understand the extent to which these studio accounts have done him a disservice – based on these recordings one might think he was a rather ordinary pianist, but nothing could be further from the truth. This concert recording of the Verdi-Liszt Rigoletto Paraphrase is an example of the stunning pianism of which he was capable in concert:

Even pianists whose recordings are amazing and critically acclaimed might not be well represented by them. One such artist is Dinu Lipatti, whose handful of lauded studio recordings fascinated me when I first encountered them. It was his sole recording of Ravel – a truly mindblowing reading of Alborada del Gracioso – that made me realize that he was a very different artist than the tales of his illness would have us believe. If only we had more recordings of him like that one, I thought – and so began my hunt 30 years ago for more unofficial recordings of the pianist. The latest cache of records obtained and released in the last decade that truly reveals that Lipatti’s official discography does not show the full scope of his playing. The handful of discs appear to be home recordings (the piano is a bit out of tune), and the abandon and vitality in these performances are in stark contrast to the highly-controlled nature of Lipatti’s studio output, with bold accents, dramatic climaxes, and emphatic gestures:

Lipatti’s most famous recordings come from the last year of his life; while his energy was bolstered by cortisone treatment for the Hodgkins Disease that had weakened him, he recorded his ‘less timing programme,’ works which did not require much exertion. He also knew that he was recording his final testament, and while the readings are very refined and musical, his playing also more guarded than that of even a few years earlier when he first began making discs for Columbia. The recently-obtained unofficial recordings were made when Lipatti was in better health and also in circumstances where he was likely less attached to the outcome: these discs appear to have been made for his own use and perhaps to share with a few friends (the numbers on the label indicate that copies were made). So as great as Lipatti’s playing is in his celebrated recordings, it may well be that how he played when in better health and when feeling more at ease was even more remarkable than how he has been perceived for decades.

Shifting Perspectives

There is another important factor as yet undiscussed and worthy of more detailed exploration in a later posting: the impact of recordings on artists’ perception of their own playing. Prior to this technology’s existence, they could only hear their playing from their own vantage point while playing their instrument and therefore subjectively and in the moment. Once musicians could hear their own playing as another listener might, able to experience details of their own performances that they might not otherwise, their perspectives surely changed. More than one famous musician has expressed surprise over how their own performances sounded (there are amusing anecdotes of famous musicians not recognizing their own recordings on the radio). Have we all not been astonished (and perhaps horrified) when hearing a recording of our voice? “Do I really sound like that?” we have all surely asked – and the same goes for musicians. How might hearing their own playing on records impacted artists’ perceptions of their own playing? Might they have thought that what they played sounded different than they had anticipated? And is it possible that hearing themselves play led to more self-consciousness not just in the studio but also in general, as their perceptions changed from that of subjective performer to objective listener?

It must be said that it is not a given that some of these changes might not have been supportive: performers can hear details that might be overlooked and strive to improve both musically and technically, whether it’s the balance, timing, or another technical element of execution. I know one first-rate pianist who records every concert in order to check on certain details and improve anything that was not as well accomplished as hoped in subsequent performances. (Tantalizingly, Dinu Lipatti hoped to record himself practicing back in 1948, writing to Paul Sacher to ask if he had a tape recorder for that purpose, which he unfortunately did not.)

Moving Forward

The ideas, thoughts, and questions presented here are beyond the scope of a website article but worthy of consideration, even if there are no easy answers – and as I’ve stated before, sometimes there are no answers but it is important to sit with questions to see what comes from them. And so, where does all of the above leave us? Perhaps with an opportunity to revisit how we relate to the act of listening to music. What if we were not so quick to judge an artist on the basis of one recording or a single concert performance? What if we let go of our need for note-perfect readings and tuned in instead to the wider landscape of what the musician is creating? What if we listened at home with the attention and dedication that would be expected of us in concert – and what if we also went to concerts more regularly in order to have that in-the-moment shared experience? While some glorious recorded performances do indeed exist and can bring us pleasure time and time again, it is the quality of the music-making that is key to its deeper enjoyment as opposed to a focus on perfection that provides us with an embalmed performance rather than an alive experience.

While there is something about perfection that is appealing, it is also wonderful to grow an appreciation for what is espoused in the ancient Chinese philosophical text, the Tao te Ching: True perfection seems imperfect. There may be what appears to be imperfections in concert settings, with noise, less-present sound, and perhaps an error made in the moment – but there is also the capacity to experience the chemistry of the moment, an alchemical act of creativity in the moment that will never be exactly repeated. The notes are but black-and-white notations on a flat page, but the music they comprise is a colourful, multidimensional tapestry that is brought to life in the moment as it is experienced by both the performers and listeners. The setting and quality of attention with which this happens has a tremendous impact on how life is breathed into the score. If music lovers wish to keep the art of classical music alive, it is important that we not be passive in our appreciation but rather be active music lovers and appreciators. Even when a concert or performance does not live up to our expectations, we might be able to find something to appreciate. Artur Schnabel was once asked by a colleague why he was clapping after a poor performance they had just heard: “I’m applauding Beethoven,” he replied. Long may we continue to appreciate and applaud the masterpieces of the past and those who continue to bring them to us.

Recent Comments