Our appreciation of pianists of the past is based primarily on their recordings. How amazing that in this age of digital technology we can listen to the actual playing of pianists born and trained in the nineteenth century— including pupils of Liszt and pianists who studied with Chopin’s students— hearing with our own ears pianism from an era that produced timeless musical masterpieces. While the names of some legendary artists who did not make recordings are still remembered beyond their lifetimes, many who had great careers are forgotten because there are no recordings, biographies, or published testimonials for later generations to reference.

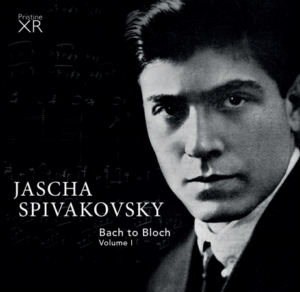

One fascinating case is that of Jascha Spivakovsky, a Russian-born pianist trained in the nineteenth-century Romantic tradition. Despite having a glorious international career spanning six decades, he never issued a solo commercial record before his death in 1970. In 2015, piano connoisseurs were intrigued when recordings made in Spivakovsky’s home were released for the first time, revealing mesmerizing playing: a magnificent singing sonority, exquisitely shaped phrasing, and probing interpretations, with an approach that paradoxically fused nineteenth-century Romantic freedom with the post-War ideal of fidelity to the score. Who was this pianist, and how could a talent of this magnitude have been forgotten?

‘A rare, oustanding talent’

Jascha Spivakovsky was born in Smiela near Kiev on August 18, 1896, and gravitated to the piano at the age of three. He studied with his father for a few years before the family moved to Odessa so that Jascha could receive professional training. The director of the Moscow Conservatory was extremely impressed with the child, whom he deemed “a rare, outstanding talent,” but restrictions on Jews entering Moscow meant that the family could not relocate there for the young pianist’s studies.

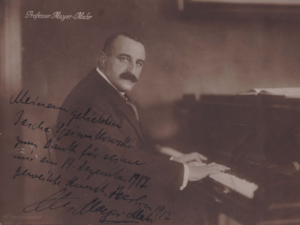

After their home was destroyed during mob attacks on Odessa’s Jewish community in 1905 (Jascha narrowly missed being shot in the head), the Spivakovskys fled to Berlin, and the young pianist was admitted to the Klindworth-Scharwenka Conservatorium, where the faculty included pupils of Franz Liszt and Anton Rubinstein. Spivakovsky was placed under the watchful eye of Moritz Mayer-Mahr, whose book The Technique of Pianoforte Playing was endorsed by Busoni and Liszt pupils d’Albert, Rosenthal, and von Sauer. Mayer-Mahr declared Jascha “without doubt one of the greatest talents of our time.”

Jascha won the 1910 Blüthner Prize at the age of thirteen (judges Busoni, Godowsky, and Gabrilowitsch sat behind a screen so as not to have any bias due to Spivakovsky’s youth), for which he was awarded a gold-engraved piano that he kept his entire life (it is still in the family’s collection, as seen here). International critics pronounced the teen “the new Anton Rubinstein” and “reminiscent of Paderewski and Carreño.” However, the young pianist’s career development suffered a setback in World War I, when he was held as a Russian enemy alien in the Ruhleben internment camp. A petition signed by the Klindworth-Scharwenka faculty eventually secured his release, and though he was paroled by Kaiser Wilhelm II, he was barred from performing until the war was nearing its end.

Escape

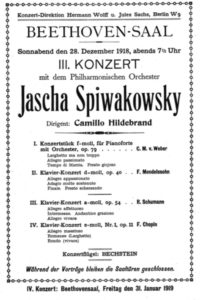

New tours brought continued success, and Jascha began performing with his younger brother Tossy, an outstanding violinist who would be chosen by Furtwängler to be the youngest ever concertmaster of the Berlin Philharmonic; the brothers would form a very successful trio with cellist Edmund Kurtz. Spivakovsky’s concerto appearances included concerts with Furtwängler and a 1918-19 series of concerts exploring the history of concerto repertoire, which sometimes included up to four concertos per concert, with the Berlin Philharmonic under the baton of Camillo Hildebrand.

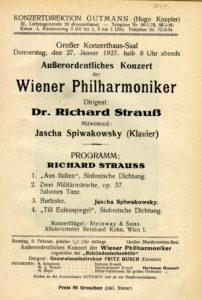

In 1926, Jascha eloped with Leonore Krantz, whom he had met on his 1922 tour of Australia, but their honeymoon was interrupted when Richard Strauss himself engaged Jascha on short notice to perform his Burleske with the Vienna Philharmonic. Their friendship may have saved Spivakovsky’s life: when the composer found out in 1933 that Jascha’s name was on a Nazi hit list, he wrote him a note with a musical passage from William Tell, a coded warning that he should escape. Jascha quickly arranged a seventy-concert tour of Australasia and left by ship just three days before Hitler became Chancellor.

Spivakovsky settled in Australia and became an important figure for classical music there. He had already made a huge impression in 1922, when he made the country’s first live broadcast of a musical performance. In Australia he was mobbed by appreciative crowds, and his stately Melbourne home became a hub for visiting musicians. Spivakovsky’s 1910 Blüthner and 1922 New York Steinway still bear the signatures of the musical luminaries who visited him over the course of decades: legendary pianists Barere, Bolet, Kapell, Malcuzynski, Moiseiwitsch, Munz, and Schnabel; violinists Elman and Huberman; singers Forrester, Galli-Curci, and Kipnis; and conductors Galliera and Szell. The thirty-one-year-old pianist William Kapell, a friend since the young American’s first visit in 1945, spent the last night of his life in Jascha’s music room prior to boarding his ill-fated flight after his three-month Australian tour in 1953.

Missed opportunities

Spivakovsky spent the better part of the period between 1933 and 1945 helping other Jews escape Germany, and he proceeded to rebuild his career after the war. He received rave reviews from top critics on his international tours—legendary British critic Neville Cardus wrote to Spivakovsky with the most effusive praise for his performance of Beethoven’s Sonata Op. 111. A health crisis in late 1960 led to his being hospitalized and then recuperating at home, and this limited his touring activities somewhat. He did play closer to home: on the occasion of a 1961 Beethoven Fourth Concerto broadcast in Melbourne, Jascha went straight from the hospital to the studio, where he recorded the performance with one rehearsal (the same day) despite not having touched the piano for weeks. That performance has now been issued, and as the second movement here reveals, he was in fine form:

Unfortunately, with limited touring possibilities due to his more sensitive health, there were fewer opportunities to record and to appear before international audiences, so his playing began to reach fewer and fewer listeners worldwide. After Jascha Spivakovsky died on March 23, 1970, at the age of 73, there was no recorded legacy to keep his name and artistry in the music-loving public’s mind.

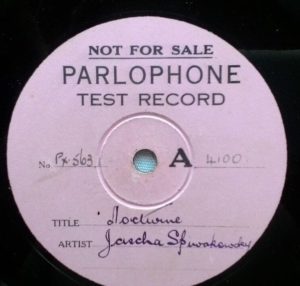

Private recordings

It is remarkable that a pianist of Jascha Spivakovsky’s standing should not have made studio recordings, but some of this was due to his own views of the process. Spivakovsky had in fact made one test recording for Parlophone in the 1920s – of Chopin’s Nocturne Op.15 No.2 and Liszt’s Liebestraum No.3 – but he was unsatisfied with the sound: this was in the acoustical recording era, when the instrument’s sound was amplified not by a microphone but a metal horn, resulting in greatly reduced fidelity. While he was willing to be recorded as an accompanist to his brother violinist Tossy’s recordings, he did not consent to release a solo recording during this period. Then, Artur Schnabel visited him in Melbourne in 1939 and recounted the stresses he endured in his process of recording the Beethoven Sonatas for EMI: on one occasion, Schnabel had showed up at the studios having prepared some works only to be told he had to record others which he had not played for some time, and he was in tears in the street after one particular recording session. His colleague’s ordeal put Spivakovsky off of the idea of recording on 78s for good.

Spivakovsky seems not to have been offered another contract until the 1950s, when a radio broadcast of a Beethoven Concerto caught the attention of some producers. Two labels hoped to release that particular performance, but the BBC quashed the idea. One company that engaged him for studio recordings folded a year after the offer had been made (the recording had been postponed due to Jascha’s touring and teaching schedule), and then a health crisis in 1960 restricted his travel and ability to follow through on a second offer. Another potential deal arose in 1969, when Tossy, who lived in New York, was offered a contract to record the complete Beethoven Violin Sonatas and he proposed doing so with Jascha at the piano. Alas, the pianist died before this could happen.

How private recordings of the pianist came to be made is a remarkable story. Jascha’s son Michael used to listen to his father practice daily, often while doing his homework in their home’s spacious music room. When he got a portable reel-to-reel tape machine in the 1950s, he decided to record his father so that he could listen to his playing when the pianist was away touring for months at a time. While he never expected that the performances would be published, he did have an inkling that there was something important about these tapes—particularly given that his father had released no commercial solo recordings.

These precious tapes came perilously close to being destroyed: when the widow of the legendary Russian bass Feodor Chaliapin posthumously released private recordings that didn’t show the singer at his best, Jascha angrily threw Michael’s tapes into the furnace, which was fortunately not on at the time. When the pianist went back to his salon to practice, Michael scooped them out and hid them in a hallway armoire. After Jascha’s death, Michael regularly pondered whether to release the recordings or not; though his father had stated that he could play better than he did in these performances, he said so at a time when he might still have been offered a recording contract – but he died without leaving a formal recorded legacy, and eventually Michael’s own son Eden convinced him that Jascha’s brilliant playing needed to be made available. Finally, in 2015 they began releasing them on the Pristine Classical label in a series entitled Bach to Bloch that features an array of repertoire as varied as the title suggests (the Bloch work will be featured in the final installment). Included in these releases are some of the few broadcast recordings that the family were able to obtain either directly from the radio stations – in Australia, New Zealand, and the UK – or which were privately recorded off the air.

This video tour I did when visiting the family in Melbourne shows the music room in which the private recordings were made, and the pianos themselves. Jascha’s son Michael shows us the autographs of legendary musicians inside the piano, the framed signed photos on the Steinway, and some original scores, and he also illustrates how he made the tape recordings of his father, with the actual device used back in the 50s and 60s:

A crystalline sonority

Whatever Spivakovsky may have thought about the privately-recorded home performances, they are musically and pianistically remarkable, featuring multifaceted music-making of the highest order: a crystalline, singing sound at every level of his broad dynamic range; elegantly shaped phrasing with a clearly defined melodic line; rubato that breathes and defies bar lines while serving the musical phrase; voicing that highlights motifs with astounding lucidity; impressive digital dexterity, with precise, consistent articulation and dazzling speed when required; thorough mastery of the pedal, which is used judiciously for colour and atmosphere without ever sacrificing clarity; and an overall sense of structural cohesiveness. Spivakovsky focuses on the minutest details—the connection between phrases, the subtlest nuance in conjunction with rubato, the decay of a note or pedalled chord—while also revealing both the entire musical structure and the emotional content of the work, a micro-macro approach that lends his interpretations a sense of authority and conviction.

Spivakovsky had an expansive repertoire, ranging from Bach to contemporary works by composers with whom he was acquainted. In works of Bach, his clarity of texture, rhythmic vitality, and terracing of motifs are utterly remarkable, reminiscent of Dinu Lipatti’s legendary performances in how both structure and content are revealed, with terraced voicing and tremendous rhythmic momentum. This 1962 broadcast performance of the Italian Concerto is a fine example, with judicious use of the pedal, brilliant use of articulation, and attentive timing further serving to clarify the architecture of the music:

Beethoven was one of Spivakovsky’s true loves – he had a rare mask of the composer above the piano in his music room – and the composer’s works were a regular fixture in his recitals and concerto appearances. Even in a work as over-heard (but underplayed in the musical sense) as the Moonlight Sonata, we hear the work as if new, with remarkably clear textures, a beautifully voiced singing line, attentive rubato, and his patented crystalline sonority.

In Chopin, Spivakovsky’s passion and attention to architecture and detail were fused to create interpretations that were clear in texture and structure while being highly emotive and personal. His use of rubato is utterly remarkable, coming at key transition times – particularly at the end of phrases and with repeated motifs. This home recording of Chopin’s Ballade No.1 in G Minor is mesmerizing – despite a somewhat out-of-tune piano – with fascinating use of rubato and an avoidance of bombast that is far too common in most pianists’ readings of this work, thereby creating a different dramatic effect. The section from 3:42 to 4:08 finds each statement of a repeated motif to be phrased and timed differently, so it is less of a mere ‘restatement’ but rather a more emotionally-infused reiteration:

Fortunately some recordings survive in high enough fidelity to showcase the exquisite beauty of Spivakovsky’s tone and the depth of his musicality. A 1954 Melbourne radio broadcast of Schumann’s Carnaval Op.9 captures the pianist’s varied tonal palette, lyrical Romantic phrasing, fiery temperament, and natural sense of timing to perfection: he uses adjustments to articulation, timing, dynamics, and tonal colour to capture the mood in varied work in the suite, be it whimsical, contemplative, mournful, or impassioned. His towering treatment of Sphinxes (at 4:47 in this link) – a section not played by all pianists – is particularly admirable for its rumbling bass that nevertheless sustains a transparent texture. Here is an excerpt from that performance:

During his years in Berlin between the wars, Spivakovsky was known as a great interpreter of Brahms, with one critic being so bold as to call him ‘the greatest living interpreter of Brahms.’ Indeed, his readings are filled with glorious rhythmic vitality and clarity of texture, his expansive phrasing never lapsing into the heaviness that has in the last number of decades been far too common in readings of this composer’s oeuvre. This 1961 home recording of the Capriccio in B Minor Op.76 No.2 was made on Spivakovsky’s 1910 Blüthner and captures with great fidelity his glass-like sonority, fluid phrasing, and refined dynamic layering. His buoyancy and vivaciousness are similar to what can be heard in recordings by pianists who knew the composer.

Spivakovsky’s repertoire extended into the works of his contemporaries – two recordings of Kabalevsky’s Piano Sonata No.3 have survived. This next work is an interesting rarity: a BBC broadcast of the Rondo Ameroso, No.7 from Harald Saeverud’s Lette Stykker Vol. 1 Op.14, which the Norwegian composer had dedicated to the pianist in 1952. This recording ca. 1954-55 is one of the few of the composition, one of only two by Spivakovsky playing pieces by the composer (both are issued in Volume 9 of the Pristine series). The BBC studio recording and beautifully regulated piano capture Spivakovsky’s refined pianism to perfection, with his rich array of tonal colours, evocative pedal effects, refined nuancing, and mindful timing drawing out the full emotional content of this lovely work.

That Spivakovsky could play with such finesse is due not only to his profound musical intelligence and training but also to an effective and disciplined practice regime. The pianist would generally work eight to ten hours a day, sometimes up to fourteen before concerts, yet he never suffered any physical strain because he played in a relaxed manner. He eschewed playing scales himself, believing that purely technical exercises took time away from practicing interpretative and tonal nuancing. While he would initially assign students scales and Hanon (the first six studies), once their proficiency improved he moved them on to Chopin and Liszt Etudes. He believed that attentive practice of these works helps students overcome myriad challenges beyond scales and arpeggios while also refining interpretation, musical expression, and tone production.

Spivakovsky’s approach to technique

Like his musical grandfather Anton Rubinstein, Jascha sat slightly high at the piano so that he could lean in to apply shoulder weight and “grip” the notes for power without hardness, not needing to resort to “slapping” at them, which can produce a hard, often metallic sound. Jascha agreed with Rubinstein that there are “a hundred ways” to play a note. Many believed that his lovely golden tone was due in large part to his thick fingers, a physical characteristic he shared with Rubinstein, but he explained that anyone can have a fine tone by carefully balancing the hands.

Bringing out the melody was of prime importance to Spivakovsky, but he abhored hearing it “banged out.” He would suggest that rather than play the melody louder, one should soften the other parts as if accompanying a singer or instrumentalist. He described projection as the difference in note strengths between the melodic line and the harmony, stating that the melodic line should be two levels above the harmony for clear projection. However, in Bach fugues, each line requires a dynamic level in accordance with its musical importance, requiring of the pianist great hand and finger balance and a superior legato facility to maintain clarity; Spivakovsky cautioned that the use of the sustaining pedal would blur lines and result in a “muddy” sound. He was always careful to highlight the melodic line, stressing the importance of emphasizing the note in chords that preserves the continuity of melody so that the line is not lost or submerged in the fabric of the work. He was also careful to make a smooth transition from one phrase to the next, often saying that any reasonable pianist can begin a phrase well, but it takes a fine pianist to end one well.

Behind the printed notes

Jascha was always concerned with seeking the “work of art behind the printed notes,” and he was critical of pianists who focused on the text without truly understanding the music. He accused them of playing “fly dirt,” meaning that if a fly had landed on the music and left a dot on the staff, these pianists wouldn’t know the music well enough not to play the dot. He felt that there was a world of difference between the indication of the artwork as outlined by the printed notes and the fully fleshed-out work of art that is the finished piece. He abhorred hearing pianism with little or no expression as much as he loathed emotive posturing at the piano, explaining that those who did so had insufficient understanding of the music to be able to express it without resorting to fake external emotion.

Spivakovsky analyzed the architecture of compositions to find their climactic points, working back from these to see how to create a sensible progression to the climax. He used several methods—accents, broken chords, tenutos, subtle changes in tempo or dynamics— to highlight these key points and make the listener aware of the musical structure. If a passage was repeated immediately, he would often play it as an “echo”—softer, slower, or both, depending upon the context—whereas just before the restatement of the main theme in a sonata, he would often make a slight ritardando to indicate that something important was about to happen. He explained that the listener is always able to discern even the slightest adjustment in tempo or dynamics, so a subtle change impels them to pay attention to what comes next.

‘Seek what they sought’

In addition to deepening his understanding of a work through the score, Spivakovsky listened to great pianists in concert and on record and he encouraged his son and students to listen to the masters as well—not to imitate them, but to “seek what they sought.” This approach highlights how he aimed not to teach others to play like him but to be individuals – and that individuality at the service of the music is what we hear in his own pianism. His highly individual signature – a gorgeous singing sound, with crystal-clear articulation, transparent and utterly consistent voicing, and magnificently forged phrasing – is recognizable in the way that the unique approaches and sound signatures of Lipatti, Cortot, and Hofmann can quickly be identified. Even if Spivakovsky’s playing at times can be so original as to raise an eyebrow, it always has its own innate logic and is tremendously musical.

Now that we can at last hear the remarkable playing of this amazing pianist and understand more about his approach to practice and interpretation, Jascha Spivakovsky can himself continue to inspire future generations to seek what he and other master musicians sought.

Many thanks to Michael and Eden Spivakovsky for their assistance with the preparation of this feature

Recent Comments