It is a tremendous blessing that recording technology has allowed the playing of great musicians of the past to be preserved for future generations. In some cases, we are able to hear performances that came perilously close to disappearing into thin air and which now form the foundation of a musician’s current reputation. One such case is the remarkable Chilean pianist Rosita Renard, whose only Carnegie Hall recital – in 1949 – is justly considered legendary and is a milestone of recorded pianism.

Rosa Amelia Renard Artigas was born in Santiago, Chile on February 8, 1894. Her abilities made themselves known at a young age and she made her debut with the Chilean Symphony Orchestra playing the Grieg Concerto when she was 14. The government would provide a scholarship the following year for Renard to study at the Stern Conservatory in Berlin, where in 1910 she would enter the master class of Martin Krause. The Liszt pupil famously taught Edwin Fischer (who was both her classmate and friend) as well as Renard’s more famous younger compatriot Claudio Arrau (it is apparently Renard who walked the young boy – nine years her junior – to his audition in 1912). After four years of training, Krause stated about Renard that ‘there is no doubt she will conquer the world as an artist,’ noting that ‘her spiritual interpretation, her sound, can only be compared with the great maestro Emil von Sauer.’

Returning to her native land at the beginning of WW1, Renard was offered an opportunity to teach in Rochester, NY but on arrival found that she had been assigned only one student. Despite this bad luck, the pianist was treated generously by admirers who arranged several concerts on her behalf, bringing her what she considered to be an outrageous sum of money – over five hundred dollars – and more flowers than she knew what to do with (she took them to Our Lady’s Shrine in a cathedral as an offering). Critics were bowled over by an all-Liszt recital at Aeolian Hall – the 22-year-old’s second at the venue – comparing her to Teresa Carreño, the ‘greatest woman pianist.’ Max Smith in the New York American wrote:

‘A more amazing, a more thrilling exhibition of bravura power than Rosita Renard gave in Aeolian Hall at her second recital, the musical public of this city has not witnessed in many a year. Indeed, since the days when Teresa Carreño first took the world by storm, no woman has disclosed such prodigious virtuosity, as the dark-haired girl of twenty-two developed yesterday afternoon in a programme devoted entirely to the transcendentally difficult works of Franz Liszt.’

With such accolades, Renard was signed to a two-year contract by Charles Ellis, who also managed Paderewski, Rachmaninoff, and Kreisler. She played in more than 40 cities in the US and her 1920 performance of the Brahms D Minor Concerto with the New York Philharmonic was praised to the skies. However, the following year Renard returned to Germany, but the musical climate had changed and she was unable to develop the same level of popularity: critics were unreceptive if not downright hostile to her, and after a few years she returned to the United States. However, she made less of an impression this time, despite playing concerts with the legendary soprano Geraldine Farrar and together with her own sister Blanca, who taught in Alabama. She played again at Aeolian Hall but did not attract the attention that had been lavished on her a decade earlier.

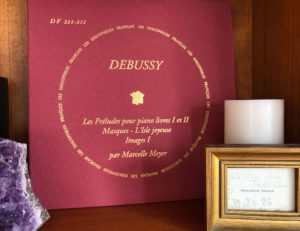

Before returning to her native country, Renard made a few recordings around 1928 – not quite as volcanic as what can be heard in her final recital, but nevertheless both bold and musical. This reading of Beethoven’s Sonata in G Major Op.31 No.1 showcases her marvellous tonal colours, deft articulation, rhythmic vitality, skillful melodic shaping, and a host of other pianistic marvels.

In Europe, she had apparently played the Schulz-Evler paraphrase of Strauss’s Blue Danube Waltz between scenes of Die Fledermaus at a New Year’s Eve party. Josef Lhévinne’s abridged disc is the most famous of the transcription, and Renard gives quite a different kind of performance, cutting the work in different areas than Lhévinne (she plays the extended introduction that is completely absent from his) and with an approach in general more fluid than her Russian colleague’s taut, bouncy reading – but of course still highly idiomatic.

Renard settled back in her native Chile in 1930, her profound modesty having led her to stop pursuing a career as a performer. Instead, she assisted reorganizing the Santiago Conservatory’s piano department while transforming a modest country home with a dirt floor into something more amenable – with mahogany furniture and elegant silver – and continuing to teach, having friends and students visit for musical gatherings on the weekend. Two more European tours were undermined by her self-effacement, until conductor Erich Kleiber in 1945 booked her for a Mozart concerto performance after her name had been proposed and he heard her play. Their rapport was such that they traveled throughout Latin America together, and Renard became known as a Mozart specialist, giving cycles in recital and orchestral appearances in Satiago, Montevideo, Lima, Buenos Aires, Bogota, and Havana (a critic in Argentina wrote that the ovation after her performance of Mozart’s C Major Concerto lasted for ten minutes).

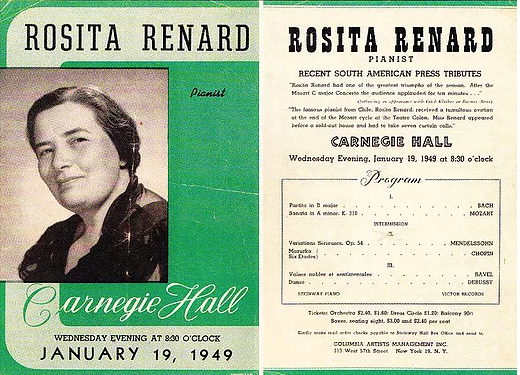

Finally after 22 years she would return to New York to give her one and only Carnegie Hall recital, the one which has now secured her place in the pianistic pantheon. Her friend Bernardo Mendel played a key role in arranging the concert: he had founded theSociety of Friends of Music in Bogota in 1945 at the suggestion of Columbia Artists Management. He had heard her prior to that time in 1944, and upon meeting her a second time, he stated that he was now resourced to help arrange a concert for her at Carnegie Hall. As usual, the self-effacing Renard was doubtful of the degree of interest in her artistry: “You are going to lose your shirt because no one is going to come to my recital. Your family and some acquaintances would go, but nobody else,” she declared. However, Mendel would not relent and insisted that Renard prepare a programme and that they meet in New York in January 1949 to go over the final details of the concert. He himself went to New York and organized the recital with Columbia Artists Management, putting together a publicity campaign that included publishing a review of Renard’s success in Bogota in the January 15, 1949 issue of Musical America which stated that she would soon “debut” in New York (a somewhat exaggerated claim: this was her fourth recital in the city – in addition to her New York Philharmonic concerto – but it was her only Carnegie Hall recital).

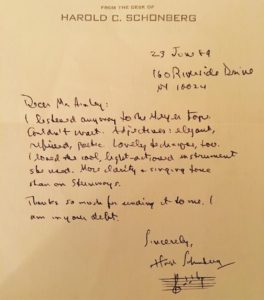

The critics were unanimous in their praise of the recital. Among them was a young critic by the name of Harold C Schonberg, who would become a leading writer on the topic of great pianists. He recalled later that he had attended and was

prepared to review a piano recital by a (to me) unknown Chilean artist named Rosita Renard. It was a fairly conventional programme that she had announced; and I while I was not prepared for the worst, I certainly did not expect anything out of the ordinary. It took the first five measures of the opening of the Bach B-Flat Partita to get the latter notion out of my head: this was piano playing of individuality, strength, and colour; perhaps not the ultimate technical word, perhaps a little too full of nervous tension, but altogether intriguing…Well, it was quite a recital, and Miss Renard received the acclaim due her.

His review at the time stated that “she likes to play fast, but this speed does not stem from a mere desire to display her large technique. It develops from a restlessness in the pianist’s mind. Her Mozart A Minor Sonata, with those fast tempi, was not orthodox; and yet, like everything else she played, it had logic and authority. Miss Renard carries the stamp of a ‘big’ pianist…”

Mendel had the recital recorded under the auspices of the Society of Friends of Music, an act that would have more important consequences for Renard’s legacy than he might have expected at the time. After the performance, Renard returned to Chile and began displaying symptoms that at first mystified doctors but which were found to be caused by a strain of sleeping sickness that was famously being treated by Albert Schweitzer in Africa. Renard herself was unable to be cured, and within a matter of months she was dead, her bright light extinguishing on May 24, 1949.

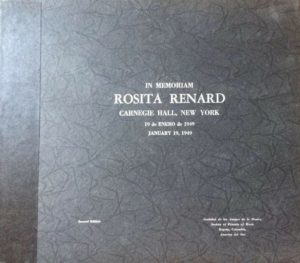

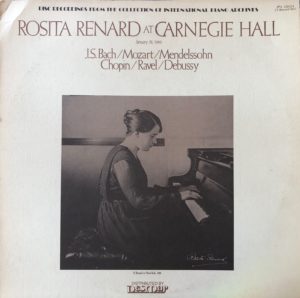

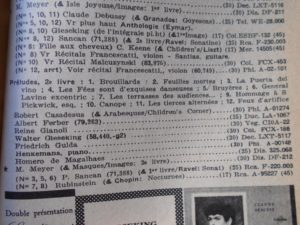

It is almost inconceivable to imagine that an artist could have faded so quickly from life when listening to the vivacious, impassioned playing from her recital a mere four months earlier. After her death, the records that had been made for Renard’s personal use were issued as a memorial volume in a two-LP set by the Society of Friends of Music. Schonberg wrote about the experience of finding the records in a New York shop, which he described as a ‘weird experience… the playback of a dead artist’s recital at which I was present; the sound of the audience, the coughs, the applause; the intrinsic merit of the piano playing.’

About a quarter of a century later, Gregor Benko would reissue the performance on a two-disc set on the Desmar label as an International Piano Archives release, and on CD on the VAI label in 1995 (the label that Benko and engineer Ward Marston released on before the latter founded his own label Marston Records). The recording has become one of the most beloved concert recordings of the last century amongst the cognoscenti of the piano world. The playing is indeed, as Schonberg remarked, full of ‘individuality, strength, and colour,’ so much so that it is almost startling to modern ears. The vitality of her rhythmic pulse, the soaring lines that put one in mind of Josef Hofmann, the volcanic exclamations that remind one of Horowitz at his most impetuous, all fused with incredible intelligence and refinement of nuance, point not only to a pianist of the most remarkable ability but also to an era in which pianism was highly individual and personal. It is almost inconceivable today that a pianist could phrase Bach’s First Partita so fluidly and romantically, play Mozart’s A Minor Sonata and D Major Rondo so briskly, be so bold and volcanic in Mendelssohn’s Variations sérieuses or Chopin Études. The playing is not for the faint of heart (I’ve said that a few times in my postings of Renard and other similar artists) and it can take a few listens – once one gets past the shock of the completely different brand of pianism that one is hearing – to fully appreciate the magic of how she is playing and the power of her musicality.

Give yourself the time to listen well to this recital – and ideally more than once – to hear a kind of music-making that has largely vanished from the concert stage of today. How fortunate we are that the miracle of recording technology makes it possible for us to hear playing that we might simply have read about: listening to Renard’s legendary Carnegie Hall recital, we can experience pianism that simply defies description. What an extraordinary treasure this is!

Many thanks to Jeff Proctor, grandson of Renard’s friend and agent Bernardo Mendel, for sharing some of the rare photographs and information included in this posting

Recent Comments